Blog

Piketty and the Charter of the Forest

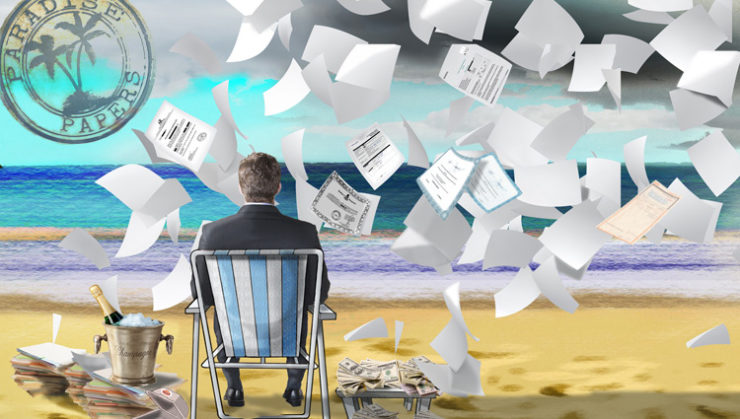

With the recent publication of the Paradise papers yet another glimpse has been given into the ways the financially blessed avoid paying their fair dues back into society. It wasn’t as if we didn’t already know this. The coverage and revelations echo closely those as a result of the publication of the Panama papers last year. This murky world of offshore, seemingly legal evasion of taxes is full of monetary transactions with political repercussions, the funding for many of the attack ads launched at the Clinton campaign, for instance. A series of scholars have been making the point that spiralling inequality, tax evasion, and the growing social unease around these issues needs to be addressed. The work of Thomas Piketty, for instance, sparked massive interest. His thesis, presented at length in Capital in the Twenty-First century, struck a chord at the time it was published. Showing that levels of inequality are peaking again after a long dip during the 20th century his point that the real problem is wealth inequality struck home. He argues for a system of global taxation and particularly stringent inheritance taxes to ensure a more equal basis of society.

With the recent publication of the Paradise papers yet another glimpse has been given into the ways the financially blessed avoid paying their fair dues back into society. It wasn’t as if we didn’t already know this. The coverage and revelations echo closely those as a result of the publication of the Panama papers last year. This murky world of offshore, seemingly legal evasion of taxes is full of monetary transactions with political repercussions, the funding for many of the attack ads launched at the Clinton campaign, for instance. A series of scholars have been making the point that spiralling inequality, tax evasion, and the growing social unease around these issues needs to be addressed. The work of Thomas Piketty, for instance, sparked massive interest. His thesis, presented at length in Capital in the Twenty-First century, struck a chord at the time it was published. Showing that levels of inequality are peaking again after a long dip during the 20th century his point that the real problem is wealth inequality struck home. He argues for a system of global taxation and particularly stringent inheritance taxes to ensure a more equal basis of society.

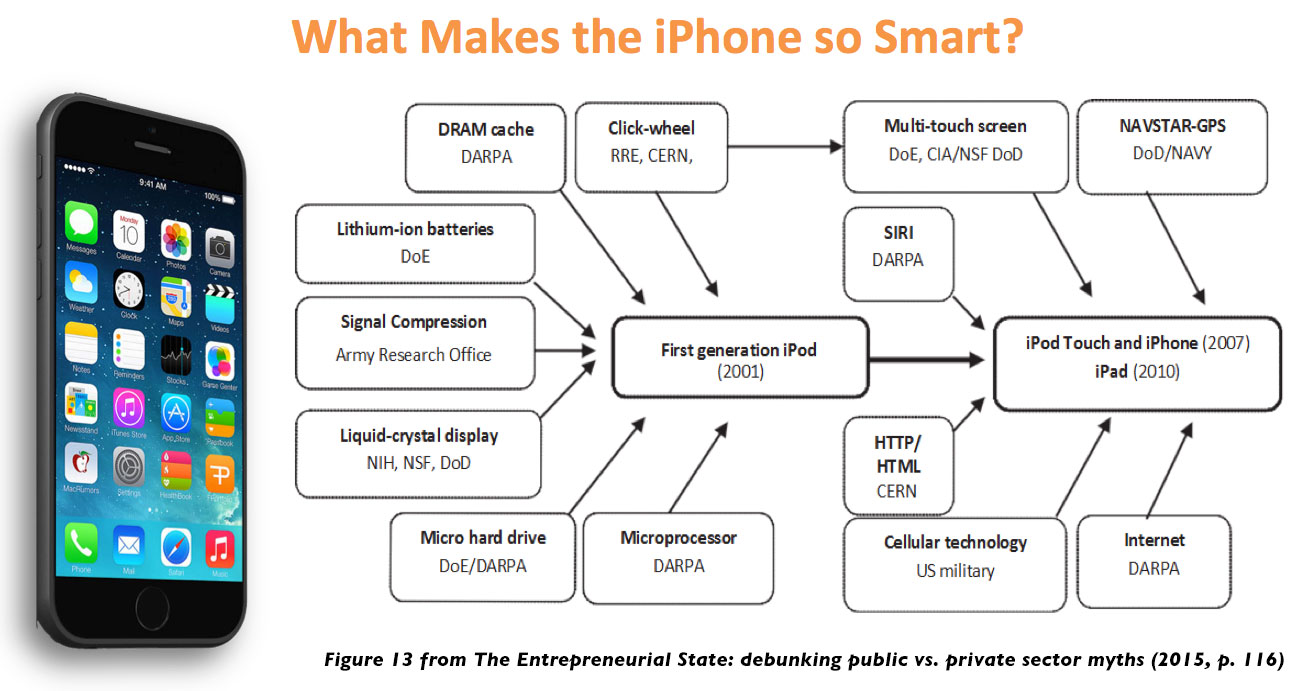

In a similar fashion Mariana Mazzucato (I am a big fan of hers), in her work on the Entrepreneurial State and inclusive growth points out that, much as we might like to believe we need to give big companies tax breaks to encourage them to invest in research and development some of the most fundamental innovation of recent times has occurred due to government investment. Taking the iPhone as an example she points out that many of the technologies involved (SIRI, GPS, touchscreens, etc.) were developed under DARPA and DoD research schemes, and combined and made profitable by Apple, who subsequently avoids paying back into the system that makes its products possible.

But what lessons can we learn from history to help tackle these problems? Today I came across this article: For a fairer share of wealth, turn to the 13th century by Felicity Lawrence (the article is a bit all over the place, dotting between the 13th century, basic income, the environment and then back to common resources but it is interesting none the less). It calls attention to the, rather charmingly named, Charter of the Forest, which was signed 800 years ago this week. In doing so Felicity Lawrence brings together the debates around inequality with another that our research group in Utrecht is closely involved in – the management of the commons. Commons are resources governed by  those who use them collectively. Originally commons referred to land used by a community for grazing, or other agrarian activities, but nowadays the term is used in many different contexts. It is a topic that, amongst others, Tine De Moor is closely involved in, and over the summer we played host to the International Associations for the Study of the Commons conference (see here). Below I have translated an interview with Tine that appeared in the Groene Amsterdammer last week and which highlights the importance of allowing citizens control over important aspects of societal organisation.

those who use them collectively. Originally commons referred to land used by a community for grazing, or other agrarian activities, but nowadays the term is used in many different contexts. It is a topic that, amongst others, Tine De Moor is closely involved in, and over the summer we played host to the International Associations for the Study of the Commons conference (see here). Below I have translated an interview with Tine that appeared in the Groene Amsterdammer last week and which highlights the importance of allowing citizens control over important aspects of societal organisation.

Translation of an article that appeared in De Groene Amsterdammer – 2nd of November 2017

Citizens are often much better at solving problems, says Tine De Moor, professor of economic and social history at Utrecht University. Her research focuses on what she calls the commons. “By commons we mean the collective management of common goods by a group of citizens”, she tells us. “If a certain good, such as clean air, a fibreglass cable or social work is managed by the government or by a company the relationship with consumers is one to one. However if they have to work together, in a cooperative form, they will have to think closely about how they are going to provide the good or service. How are you going to effectively regulate usage? How can members make claims for consumption? You can’t fall back on judicial rules. You have to set up your own institutions. Any mistakes will have big ramifications for the group. For this reason you often see that when goods are collectively managed this is done so more efficiently than a government or company would be able to. “

In the history, time and time again, we see citizens establishing cooperatives, repeatedly when the market failed. “We see the first wave in the Middle Ages, with the establishment of guilds. These were eventually all abolished as there was a feeling that you shouldn’t leave such matters to citizens. The second wave can be seen at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century. Think of Achmea, housing cooperations, the agrarian lending bank (Boerenleenbank), the precursors of Campina (Dutch dairy producer), the trade unions and the sports associations. But here again, in the course of time, we have seen the cooperative element strongly diluted. In a neoliberal climate the expectation is that the market will be able to do everything better.”

It now seems like we are seeing the start of a third wave, says De Moor. “People have yet again discovered how fallible the market is. Villages slowly dying as their populations depart, care-systems that are being brought back to absolute basics, sustainable energy projects that don’t seem to come to fruition: since 2005 in the Netherlands and elsewhere cooperative initiatives to tackle these issues have sprung up like mushrooms. People want to try and solve the problems that the government and the market have left untouched. The big question is: will the children of the second and the third wave be able to work together? The children of the second wave, housing cooperations for instance, think mostly in market terminology and see the new-comers as a burden. The third wave is often very idealistic and rejects the market outright. Will the two movements be able to join forces? The answer to this question is crucial.”

End of translation

This brings us back full circle to the Charter of the Forest – renegotiating the terms of the social contract is something that the combined forces of the second and third wave participants might be able to play a role in. And who knows, maybe we will see a revival of the right to pannage (pasturage for pigs) in the near future.

Leave a Reply