Blog

From households to factories: Who makes our clothes?

An interesting concept in social science is “alienation”. We are unaware of how the products around us came into being and so we are alienated from the majority of products around us. Take our clothes, for example your t-shirt, jumper and jeans. Our clothes were historically made at home; cotton was farmed, spun and weaved on hand looms in the household by women and children. Today we hardly know who made our clothes, nor how they were made. Sometimes disasters such as the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh make the news and force us to examine our spending habits, but cognitively it is difficult to think about who makes all of our fabrics (somehow the words “made in China” don’t really make things any clearer, given the size of China ), why people do so (to eat or to buy the latest iPhone?) and where. The common image of the factory worker without any agency or option but to work, may make sociologists’ lives easier, but unfortunately they may not be completely right.

In the 19th century specialization and innovations (think Spinning Jenny) led to workers slogging away in the factories in the North of Lancashire, in England. Having grown up in Lancashire, it’s clear to see that there isn’t much left but derelict mills and the time warp back into the ’90s – that is Blackpool pleasure beach – where mill workers went on their one day off.

Blackpool pleasure beach – a pioneering part of George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse

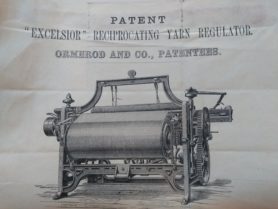

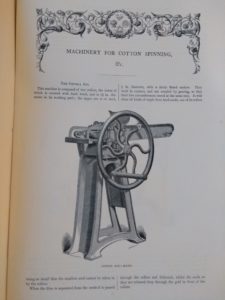

Cotton and textiles have historically played a massive role in our lives, both at the household level and for the “development” of countries through industrialization. This podcast provides an interesting discussion on textile history and its relevance in todays world. Below you can see the kind of innovations that came about in the 19th century. For more examples see ‘Papers related to the textile industry’: GB 133 Eng MS 1185 at the John Rylands Library, Manchester

In my research, I look at how and why workers in the UK went from making textiles at home and ended up in the factories. However in China where there were many similar conditions, this shift was not as definitive. Today a large part of textile production still takes place in smaller rural production units (contrary to dominating industrial image the media usually shows us). For a more visual example of this, you can watch a silk handloom weaver in China here.

I’m personally interested in this project as my parents came from Gujarat, India (formerly and still a textile powerhouse) in the 1970’s to work in the cotton mills and to this day a large Indian community still work in textiles at homes. (Unfortunately household work does not feature in statistics such as GDP but it still exists.)

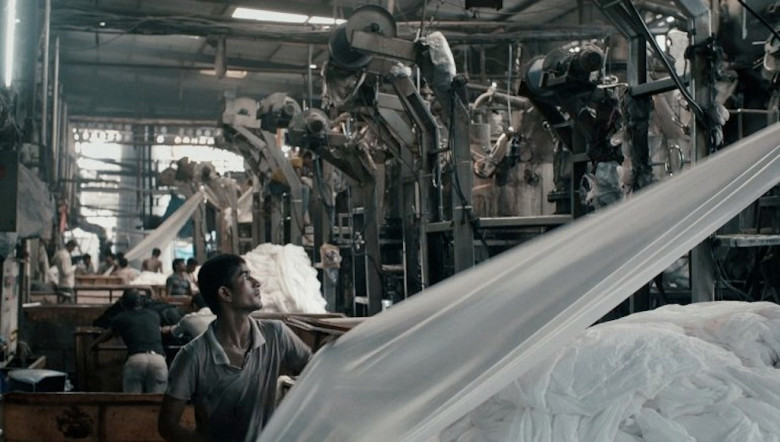

I highly recommend Rahul Jain’s documentary Machines (2016) for an in depth look at contemporary Gujarati textile workers

In the next few months I aim to keep readers up to date with my research in both the UK and China and provide a breakdown of the main debates amongst historians.