Blog

History of (un)happiness

By Jan Luiten van Zanden

Someone who commits suicide is extremely unhappy.

The happiness industry has also made abundantly clear that people are unhappy

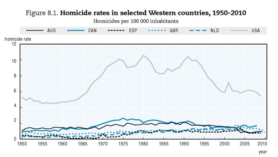

The number of victims of violent crime has plummeted.

Have we become madder since Freud?

How did people feel in the past?

Suicide, prisons and psychiatric patients.

A history of unhappiness

It’s difficult for historians to determine how happy people were in the past. We can’t ask them and they seldom wrote about it. But for certain groups we can conclude that they were unhappy. In such a way an index of unhappiness could be constructed for the past.

The economic performance of a country is frequently measured in terms of national income per head of the population. Historians, following in the footsteps of economics such as Simon Kuznets and Angus Maddison, do the same. Both Kuznets and Maddison were both pioneers in the history of the study of national income. But increasingly this approach has come in for critique, largely becomes income is only one of the many dimensions of wellbeing.

Economic historians have taken this critique on board and have attempted, in various ways, to chart the long term development of multidimensional well-being in certain countries and in the world as a whole. One of the places that this has been attempted was in a report for the OECD (How Was Life). Here we looked at life expectancy, the quality of the living environment, schooling, exposure to crime and a number of other factors that determine the quality of existence.

One can collect data on almost all facets of wellbeing, although some may prove more challenging than others. But what we cannot measure is how happy people felt – the subjective wellbeing experience – in the past. In conversations with OECD experts the question was frequently raise: can one not measure happiness in the past?

You can look at how often terms like happy and happiness appear in large historical databases like Delpher, containing virtually all newspapers published in the Netherlands. Happiness seems to be an invention of the Enlightenment – people in the 17th century apparently did not ask themselves whether they were happy or not. But what does this say about the happiness of a Dutch (or foreign) citizen in this period? Can you be happy without knowing the term happiness?

Psychiatric wards

We will, I think, never know as interviewing those alive during the seventeenth century remains challenging. But maybe, I realized when I was asked to write this piece, we can approach the question of happiness from a totally different direction. We don’t know how happy people in the past where, but maybe we can say something about how unhappy they were. And we can do this not by interviewing anyone but by looking for observable behavior.

Someone who commits suicide, for instance, is likely extremely unhappy – although whether an individual goes so far as to follow through with the act depends on the norms and values of the society (in Greek and Roman antiquity suicide was much less taboo than during the Middle Ages). Someone who is in prison will be relatively unhappy, seeing as that is the essence of being locked away: punishing people for aberrant behavior and therefore partially reducing the quality of life (freedom) of the individual. In the distant past criminals were rarely locked away for long periods of time but were rather banished or condemned to death. In this way they disappear from the records – a factor that should be considered.

Victims of violence are the third, extremely unhappy group. The fourth is psychiatric patients – even if they are not locked up (at this point I always have to think of the opening scenes of my favourite film, Amadeus, which are set in an imagined eighteenth century psychiatric ward. Those who know the film gets the picture).

know the film gets the picture).

Conciously Unhappy

We could follow these four groups of the “unhappy” through the ages. How has the phenomenon of suicide developed? Why do some countries – the USSR after the fall of the wall for instance – experience epidemics of suicide? Why are their more suicides in countries with long, dark winters? To what extent has suicide increased or decreased over time?

The hypothesis could be that with the advent of the term “happy”, and as the norm that people should be happy became steadily more important, that people became more consciously unhappy – or at least aware of the fact they were unhappy. In other words, the happiness thinking that emerged during the Enlightenment also made clear that there were unhappy people. Unhappy people who were, in the most extreme cases prepared to take the most extreme measures. According to this logic there should be few suicides before the 18th century. Intuitively I think this is correct but has anyone ever looked into this?

Suicide is probably the purest indicator of “unhappiness”. Prison populations capture something slight different, in the sense that there is an important role for the repressive nature of the state – also a factor in the wellbeing of the population. What does this say about the unhappiness of Americans, where the number of inmates per head of the population is far higher than elsewhere, a trend that started in the 70s (when Nixon launched the War on Drugs).

Russia and Cuba have been fighting it out for the second most prisoners relative to their populations (if we ignore small countries with extreme numbers such as the Seychells and the Maldives – should you still wish to take one of these on board in your holiday plans). Maybe it is prejudiced but it wouldn’t surprise me if Russia (with its Gulag archipelago and banishment to Siberia starting in the time of the Tsars) had a historical claim to first place in this measure.

A historical miserableness index

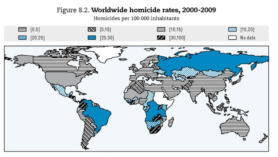

For the OECD report mentioned above we have already set out what we know about the frequency of murders in the past and today. Over the long term violence has declined, and the decline in the frequency of murders is a good example of this decline. As a result the number of victims of violence has fallen sharply, although in the US this is far less the case than in “civilized” Western Europe. Russia, Brazil and South-Africa are currently amongst the most dangerous places in the world, with homicide rates three to four times higher than that in the US (see here).

The history of the locking up of psychiatric patients is too complex to summarise here. And whether or not. And whether or not an individual was locked up doesn’t say much about the underlying problem of psychological illnesses and how frequently these occurred. Do we have any idea of whether these have increased over time? Have we become crazier since Freud or less so? And what do we know of international patterns which are so clearly observable in other groups of the unhappy?

To relate this back to the measurement of historical (un)happiness: if we could get hold of the details of these groups of the unhappy we could develop an alternative, historical miserableness index, the counterpart of the happiness numbers that are currently generated by researchers looking at subjective wellbeing. I think that, on the basis of the information currently available, Russia would stand a good chance of gaining the top spot in this index. It would be interesting to explore whether unhappiness measured in this way has increased or decreased over the long-term.

In closing: maybe this is more than a hobby-horse of historians who would like to say something about happiness and unhappiness in the past. Someone closely involved with the “happiness industry”, an academic who concerns themselves primarily with measuring happiness, once confided in me that the most important conclusion of this sort of research is that we can’t change much about the happiness of the average person.

If we want to improve average happiness than we need to invest in the happiness of the extremely unhappy – of psychiatric patients, violent criminals, victims of crime and the potentially suicidal. In addition to improving average happiness there are strong ethical grounds for doing so, at least for those who believe in an equitable distribution of happiness.

In How Was Life? Global Well-Being since 1820 a group of historians, including Jan Luiten van Zanden, researched well-being of the human populace of the world using 10 factors. Health, for instance, can be measured using height measurements, education by the degree of literacy. One of the conclusions of this research, conducted for the OECD, is that the differences in world-wide wellbeing have become smaller, while those in income inequality have increased.

Jan Luiten van Zanden is professor of economic and social history at Utrecht University. He conducts highly innovative research into the economic history of the Netherlands and Indonesia, and has reconstructed national accounts for the period 1800 to 1940. In 2003 he won the Spinoza prize, in part due to the large international projects that he has established and led.

Van Zanden pays a lot of attention to the measurement of welfare today and in the past. In collaboration with the Rabobank, he and others at Utrecht University developed the Broad Welfare indicator (BWI) which was launched in 2016. The BWI doesn’t only measure the economic situation of the Dutch but also takes into consideration other factors that determine wellbeing, such as employment opportunities, job security, education, health, environment, housing, safety, political participation and happiness.

If you are interested in this or similar research please take a look at the links below:

Keith Snell (University of Leicester), ‘Loneliness in history: exploring ‘solitaries’ and ‘singletons’.